What happened

In 2020 one of my colleagues brought up the fact that the University of Windsor did not have digital access to the Windsor Star, the newspaper of our home city. Earlier in that year I had done a cursory review of the ProQuest Historical Newspaper platform, a database of digitized newspaper microfilm. That early review showed that the bulk of the usage was attributable to only two titles. Like most libraries, the best way to fund new e-resource acquisitions is to swap titles, so a more thorough analysis was conducted. Working with a small team of librarian colleagues, we set out to evaluate the resource and the potential to swap.

We had access to 10 U.S. newspapers through two packages through CRKN, and directly subscribed to 2 titles with the vendor. The library owned the perpetual access rights to these titles and was only paying for hosting fees on the platform. The hosting fees for the 10 titles were very expensive, and could cover the one-time purchase cost of the long-needed title. Since this was a resource negotiated through CRKN, I reached out to learn more about the agreement and the history of the resource. It turned out that there was no way to separate the hosting fees from the subscriptions for some of the other titles. For access on the vendor’s platform, we must pay both fees – an expensive option. We had negotiated the rights to locally load the content (host it ourselves), but after consulting with a colleague and examining sample data provided by the vendor, we decided this was too expensive to accomplish.

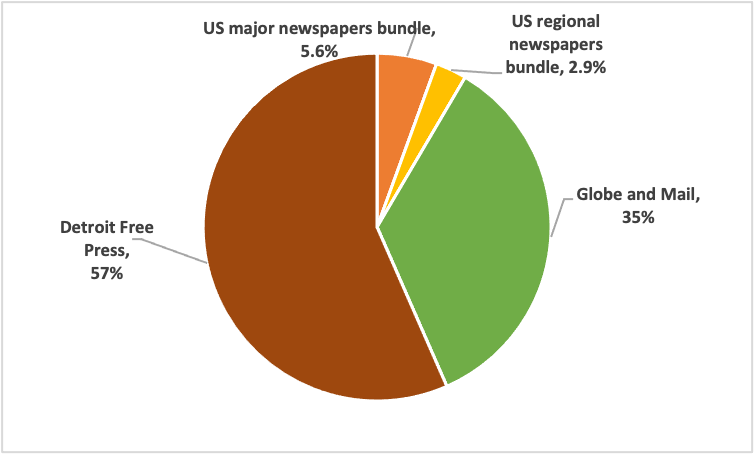

With a closer look at the usage data, I found that 92% of the usage came from just the 2 newspaper titles we subscribed to outside of the consortial packages. It was clear that there was a potential option here: cancel the subscription to one or two of the packages and use the savings to fund the purchase of the Windsor Star. I requested a trial of the resource and explored its features. We found the imaging to be good, and it provided unique content not found elsewhere. I put together a proposal for library administration and for the librarians, and presented this during a meeting to all. During this meeting some librarians expressed their concerns over losing access to historical newspaper content, but there was no knowledge on which titles were most important.

Our plan was to consult widely with faculty and graduate students at the university, and understand how this resource was used, by whom and which titles were most essential. I launched a webpage that explained our rationale, process and the evaluation openly. Notices were placed on the database records and librarians were provided a form email to send to their departments. We received around 20 responses, with most identifying the same 3 titles as essential: The New York Times, Washington Post and Wall Street Journal. Fewer respondents indicated usage for the rest of the titles, a package of regional U.S. newspapers. With this information in hand, we decided to retain the 3 newspapers and take a closer look at the rest.

While keeping their liaison librarian in the loop, I contacted the handful of respondents who indicated a need for the other newspapers. In their initial emails, some of the respondents had expressed grave concerns over the potential loss of these titles, going as far to ask the Dean to advocate on their behalf. I scheduled video calls to discuss the matter, and understand their needs while providing more data and information on the usage. The faculty members appreciated being briefed on the matter and that we had already incorporated their feedback to retain the 3 titles. During these conversations I discovered that some faculty members were using the niche titles for their research, and that cancelling would cause them to lose access to a valuable dataset. I noted all of the titles that were necessary and explored if there were other options available. While ProQuest holds a monopoly for these titles in the academic market, I discovered that for these niche titles backfile access was available to individuals through newspapers.com at a cost of $100 per year.

I communicated the availability of these titles elsewhere to the faculty members, and provided them with a trial to the platform. These faculty members were enthusiastic in finding an alternative source for these titles, through a personal subscription that provided them with access to tens of thousands of other titles at a low cost. In the end, our more vocal critics became enthusiastic supporters.

I compiled a list of titles to aim to retain during re-negotiation with ProQuest, based on the email responses. I noted that one of the titles, the Chicago Defender, was our only subscription of a Black community newspaper in the collection – an important primary source reference. I prepared a negotiation strategy that followed best practices in coordination with administration, outlining our goal and the possible scenarios, including our option to walkway if a negotiated agreement was not possible. Because of the in-depth evaluation with our users, we were comfortable in knowing that if negotiations were not successful, we could walk away with a minimum number of titles and access would be preserved. In the negotiation we expressed our needs and principles behind the decision to de-bundle the packages. We communicated that the perpetual access model did not work with us, and that we didn’t need most of the titles. We wanted to arrive at a deal with a smaller set of titles. Ultimately, the vendor could not provide us with an offer that met our needs so we cancelled one of the two packages, and walked away from the other – retaining subscriptions to the Chicago Defender, the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Wallstreet Journal.